Industrial systems often require continuous operation, where even a brief downtime can be costly. Even protocols that were traditionally more lax have over time introduced strategies to improve or bring about high availability and tighten security.

In OPC-UA redundancy is a concern in order to guarantee the maximum up time possible. In the past OPC-UA servers have been tightly coupled either with the physical hardware of the machine or very near it. This makes redundancy rather pointless, as if the machine is in fact not operating, having a running OPC-UA server won’t be of much help.

With the continuous improvement of PLC capabilities, OPC-UA is now also being used for line or multi-machine scenarios and even for abstraction layers of other OPC-UA servers. As OPC-UA goes farther from the machine, redundancy becomes a greater concern.

In this article we are going through what OPC-UA specification guidelines on how we can build redundancy of OPC-UA servers.

Overview#

First off, if we have no redundancy strategy when your OPC-UA server goes down, all your OPC-UA clients will lose their connection and session.

In OPC-UA, redundancy means devising ways to have backups to our server going down. Redundancy can be crucial in scenarios where systems must run 24/7, because it eliminates the single point of failure at the server level. In OPC-UA high availability is always guaranteed by somehow running redundant server sets, let’s see what are the ways this can operate.

OPC UA defines two general modes of server redundancy: transparent and non-transparent. The difference lies in who handles the failover.

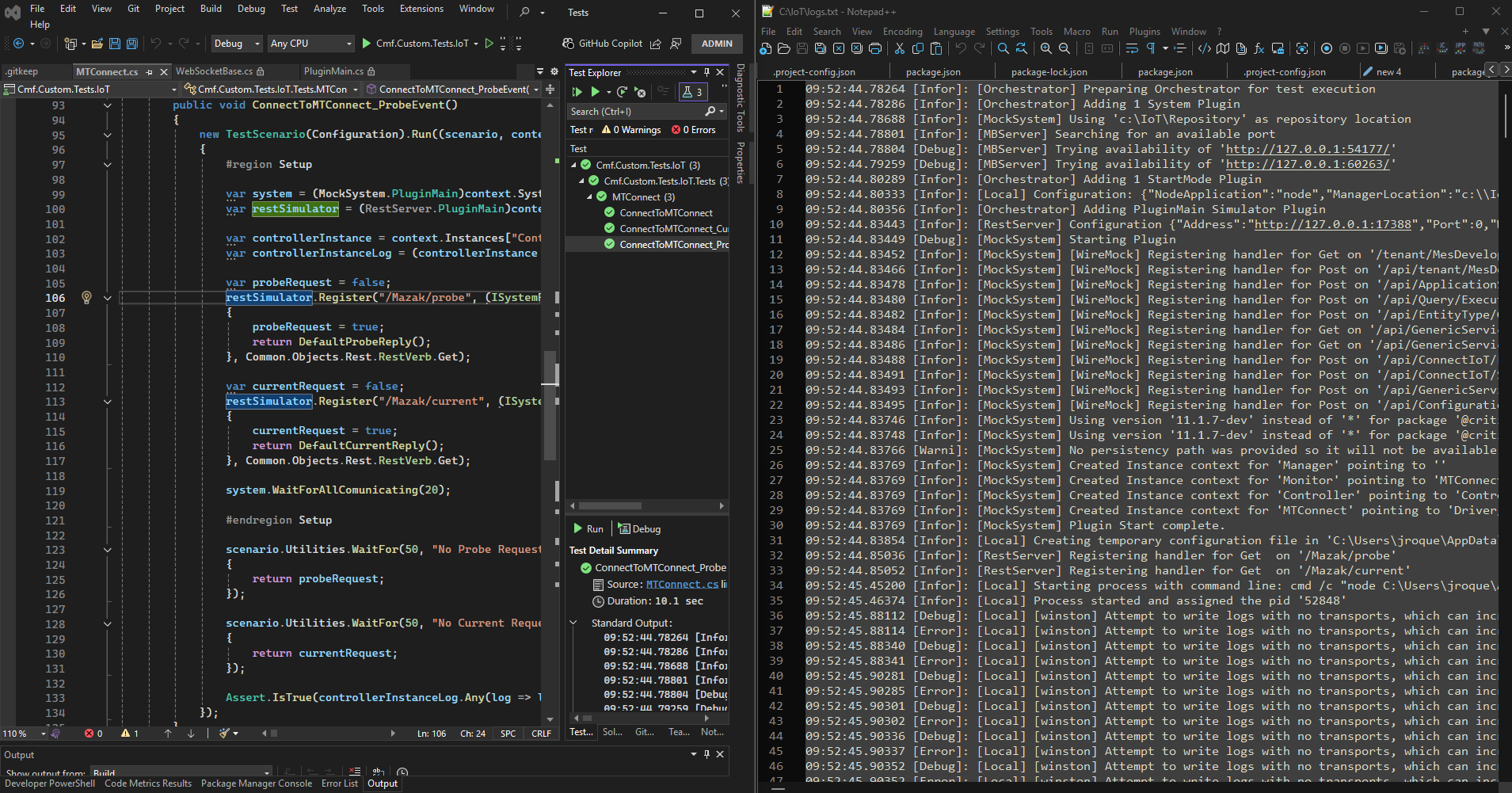

In transparent redundancy, the switch-over from one server to another is hidden from the client – the client isn’t even aware a failover occurred.

In non-transparent redundancy, the client is aware of the redundant servers and is responsible for detecting a failure and reconnecting to an alternate server.

Both approaches aim to keep data flowing, but they place responsibilities on different parts of the system. We’ll examine each approach and the specific standby modes that non-transparent redundancy supports.

Transparent vs. Non-Transparent Redundancy#

Transparent redundancy is the mode more analogous to other classical architectures. Where the client does not need to know that is being rerouted to a different server. In most web applications, when accessing a URL that is behind a proxy able to load balance, he will direct your request to whichever host is available to serve you, without the client having any idea that is being rerouted or if there are servers up or down.

In a transparent redundancy setup, all servers in the group present themselves as a single server to the outside world. They typically share one Server URI and one Endpoint URL (often achieved via a virtual IP or network load balancer). The client connects as if to a single server and does not need any special logic to handle failover.

Failover is handled by the infrastructure or cluster: when the primary server fails, the system automatically directs client communications to a backup server. The client continues sending and receiving data as normal, oblivious to the switch.

The advantage of transparent redundancy is its centralized approach any OPC UA client can benefit from redundancy without modification.

The downside is the complexity on the server side and network: you need a robust clustering setup (for example, a virtual IP address or network load balancer that fronts multiple servers) and typically a mechanism to keep the servers’ state in sync.

Even though it has a lot of advantages and this architecture is ubiquitous in the web world, for OPC-UA transparent redundancy is less common in practice because of the higher infrastructure effort.

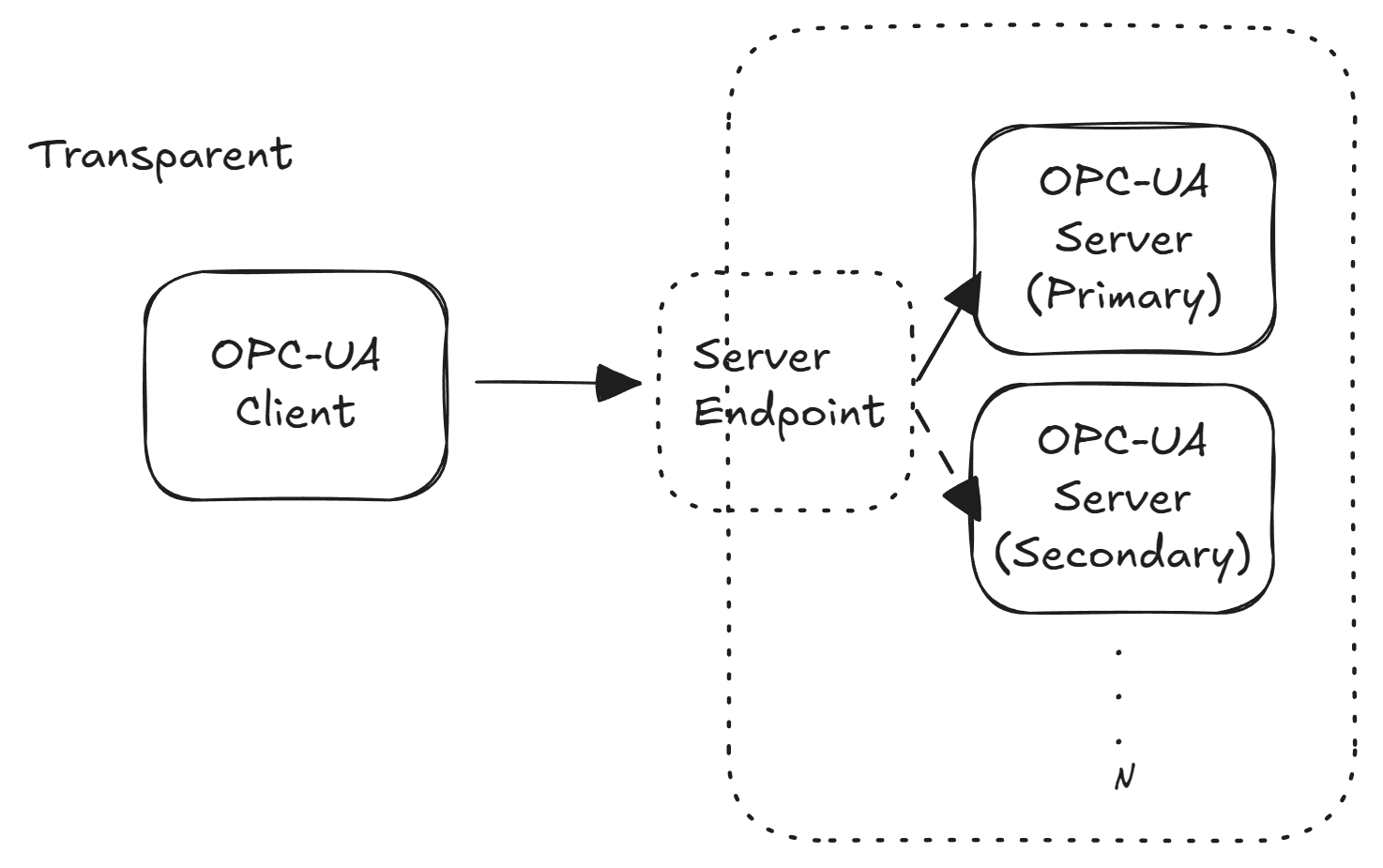

In non-transparent redundancy, each server in the redundant set has its own network identity (unique endpoint URLs and Server URI). This is already a big difference from transparent mode, as it delegates responsibility to the client of being aware that there are multiple endpoints able to serve.

Therefore, the clients must be redundancy-aware, it knows about multiple servers and takes action during a failover. Essentially, the client manages the redundancy.

OPC UA provides standard structures in the server’s address space so that a client can discover the other servers in the group and understand the redundancy configuration. Each server exposes a ServerRedundancy object that indicates the redundancy mode and lists the servers in the set. Using a standard discovery service, the client can retrieve the Application Descriptions (endpoints) of all servers in the group.

This means the client can connect to one server initially and learn about the backups automatically, rather than being pre-configured with all server addresses. The client then monitors the health of the current server and switches to a backup server if needed.

Non-transparent redundancy shifts complexity to the client, but it gives the client fine-grained control over failover timing and selection. Modern OPC UA clients or middleware often include logic to handle non-transparent failover.

Transparent redundancy requires a more sophisticated server clustering but lets even simple clients achieve high availability with no special code, but it guarantees absolutely no interruption in client connectivity. Non-transparent redundancy is easier to implement on the server side (no cluster IP needed) but requires clients to be aware of redundancy and handle reconnection logic.

Redundant Server Sets and Data Synchronization#

When configuring any OPC UA redundancy (transparent or non-transparent), all servers in the redundant set must behave like identical twins from the client’s perspective.

The OPC UA specification requires that redundant servers have an identical AddressSpace, including the same NodeIDs, browse paths, and data structure. In other words, the information model and data provided by Server A should be indistinguishable from Server B.

This is critical: it allows a client to seamlessly switch servers without having to re-discover nodes or fix broken item references. If any changes to the address space occur (adding or removing nodes), they should be propagated to all servers in the group to maintain consistency. If by any chance they are not the same, the failover to the new server may not work or provide inconsistent data to the OPC-UA clients.

Beyond the address space, servers in a redundancy group must keep certain runtime data in sync to avoid inconsistencies. Time synchronization is important, all servers should have synchronized clocks (using NTP or PTP) so that timestamps on data and events are aligned.

For example, if one server is a few seconds off, a client switching over might see timestamps jump backward or forward, which can confuse time-series processing. Another subtle issue is Event synchronization: in some redundancy modes, each server might generate events (alarms, conditions) with unique identifiers. If not handled, a client could mistakenly process the same real-world event twice after a failover (once from each server, with different Event IDs). The OPC UA spec addresses this by requiring that in fully synchronized modes (Transparent and HotAndMirrored), servers coordinate their EventIds to be unique across the cluster. Similarly, historical data or any buffered data should be kept consistent if possible, or the client may need to reconcile data from before/after the switch.

Another key concept is ServiceLevel. This is a standard variable (Byte value 0–255) exposed by each server to indicate its current ability to serve data. Think of ServiceLevel as a health or priority score: the primary server will typically report the maximum value (e.g. 255) when fully operational, while a backup server might report a lower value (or 0 if not ready). Clients can read or subscribe to ServiceLevel on each server to decide which server is “active” or to detect when a server becomes unhealthy (ServiceLevel dropping to 0 or 1 signals a failure in some implementations). Ensuring all redundant servers correctly update their ServiceLevel is a best practice, as it provides a simple trigger for failover logic on the client side. Some vendors use fixed ServiceLevel values for primary vs. secondary (for example, one vendor’s redundant PLC OPC UA server sets primary = 255, secondary = 227). The OPC UA specification doesn’t fix exact values for each role, but it mandates that the highest ServiceLevel indicates the server currently able to supply data, and that value changes appropriately on failure or recovery.

In summary, a redundant server set (or redundancy group) is a group of OPC UA servers presenting one logical data source. They must mirror each other’s address space and keep important state synchronized. As we saw, this may not be a trivial solution.

Non-Transparent Redundancy Modes (Cold, Warm, Hot, Mirrored)#

Non-transparent redundancy supports several failover modes that define how the backup servers operate relative to the primary. These are commonly referred to as Cold, Warm, Hot, and HotAndMirrored redundancy. The modes differ in how actively the secondary servers run and how fast a failover can happen.

Let’s explore each mode:

Cold Failover#

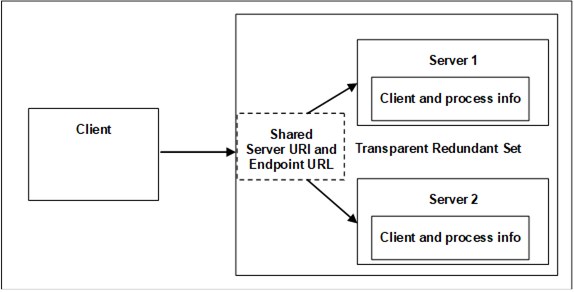

In Cold redundancy, only one server is active at any given time, by itself it does not avoid some data loss.

The backup server(s) are essentially off or not running the OPC UA application until needed. This could mean the secondary servers are powered down, or the machines are on but the OPC-UA server software isn’t started until a failover.

If the primary server fails, a backup must be started and then the client connects to it. This involves the longest delay and as the name implies is related with having a cold start of the backup OPC-UA server.

The client can only be connected to one server at a time in cold mode. Upon detecting a failure (for instance, the client loses its connection to the primary), the client looks up an alternate server from the redundancy information and attempts to connect to it.

The failover isn’t instantaneous, there will be a gap while the backup server initializes and the client establishes a new SecureChannel, session, and subscriptions. Data loss or missed updates are possible in this gap. Cold standby is the simplest to set up (only one server runs at a time), but it provides the lowest continuity. It’s suitable when downtime can be tolerated for a short period or when hardware resources are limited.

Think of cold standby as having a spare server in a closet that you boot up when the primary fails, can be effective but not quick.

From the client perspective, cold redundancy means the client only needs to maintain a connection to the active server. The OPC UA client should cache the list of backup server endpoints (provided by the ServerRedundancy object) and be prepared to create a new session on a backup when the active one disappears. No background communication with the backups is needed during normal operation. The trade-off is that on failure, there’s more work: the client will establish a fresh SecureChannel and Session to the backup, and then re-subscribe to all data items, which takes a certain amount of time, that time is variable based on the amount of data items being subscribed and the capabilities of the machine running the OPC-UA server.

Warm Failover#

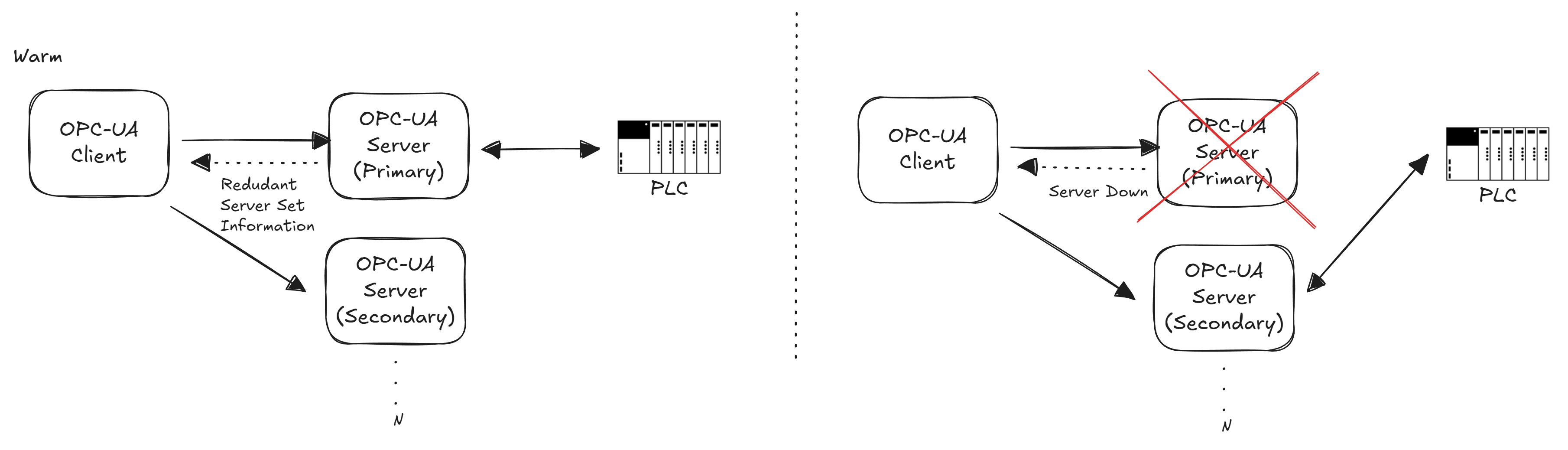

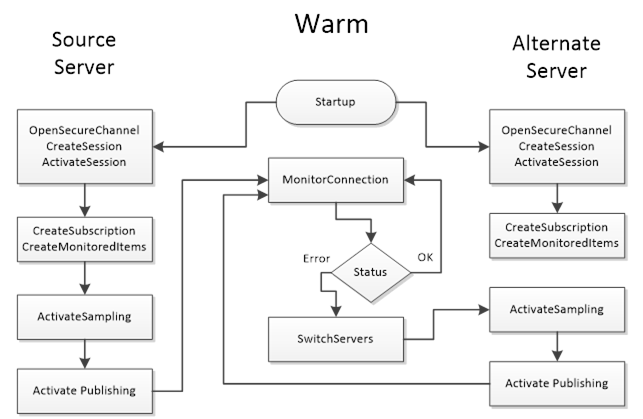

In Warm, the secondary servers are running and available, but they are not actively pulling data from the field devices while the primary is active.

This mode is common when the data source (e.g., a PLC or controller) can only accept one connection at a time, the backup servers stay ready but refrain from connecting to the PLC until they become active.

In warm standby, a client will typically connect to the primary server and may also open connections to the backups purely to monitor their status (for example, reading their ServiceLevel). Only one server (the primary) actually provides data to clients. The others might return a placeholder or an error like !Bad_NoCommunication!, if you tried to read actual data from them while they are in standby. This indicates they are online but not presently sourcing data.

If the primary fails, one of the backups will take over the active role. The transition in warm mode is faster than cold because the backup server’s process is already running, there’s no need to start the application from scratch. However, since the backup was not pulling live data until failover, there could still be a short interruption and some data might not be collected during the switch.

For clients, warm redundancy implies maintaining at least a minimal connection to each backup server before a failover. A best practice is to create a session (and possibly subscriptions in an inactive state) on the backup server(s) in advance. The client can periodically check each server’s ServiceLevel value to see which one is primary (the one with the highest ServiceLevel is active). During normal operation, the client receives data only from the primary. On a failover, the client should activate subscriptions on a backup server (or create them if not pre-created) and start receiving data from it. Because the backup server might need to connect to the device (e.g. PLC) at failover time, there could be a brief delay.

Warm mode strikes a balance between resource usage and recovery speed – it’s widely used when devices cannot handle parallel connections, but high availability is still required.

Hot Failover#

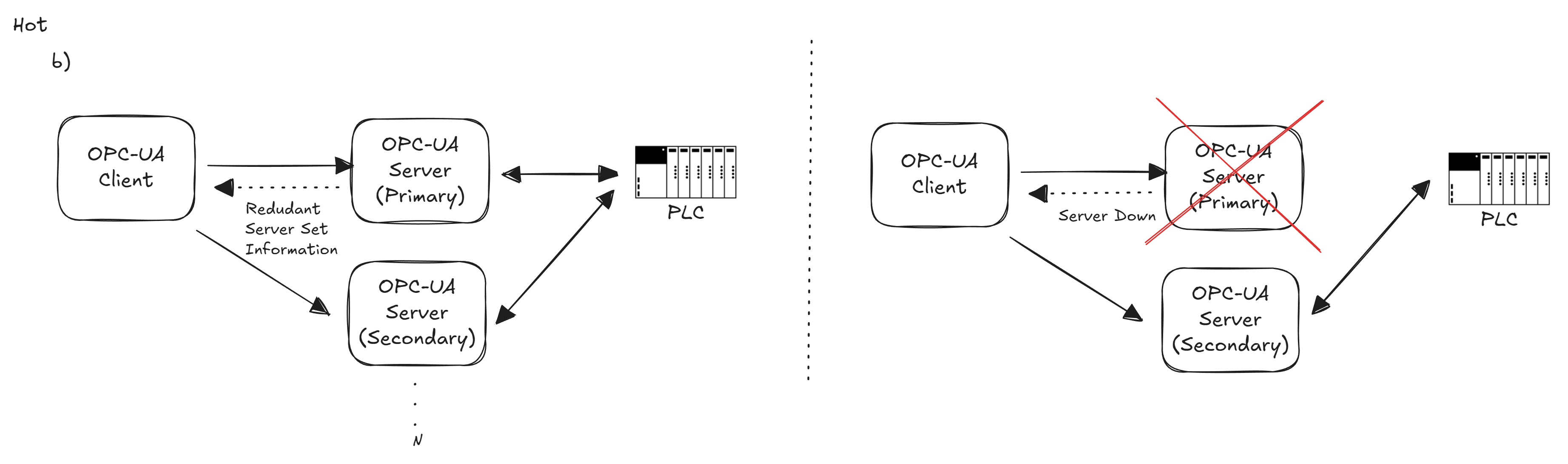

In Hot redundancy, all servers are fully active and acquiring data in parallel (assuming the devices/protocols allow it).

Every server in the redundant set is powered on, running, and typically connected to the data sources (for example, multiple OPC UA servers all reading from the same PLC or sensor network simultaneously). Because of this, a backup in hot mode already has current data at the moment of failover. If one server fails, the client can immediately switch to another that has been getting the same updates, resulting in minimal to no data loss.

The servers in a hot set operate independently, with only minimal knowledge of each other, mainly they might be aware of each other’s existence and health, but they don’t necessarily share runtime state (beyond possibly some coordination of ServiceLevel or who should be primary). When a server encounters a fault and drops out, its ServiceLevel will drop to a low value, signaling clients that it’s no longer suitable. Conversely, when that server comes back, it will announce itself with a ServiceLevel indicating it’s available again (likely as a backup until it catches up or is manually restored to primary).

Hot redundancy generally provides the highest availability short of full state mirroring. However, it requires that the underlying devices or data sources can handle multiple concurrent connections. Not all PLCs or sensors allow that, so you must verify device capability (or use a data aggregation mechanism) for hot mode to work. Additionally, running all servers in parallel consumes more bandwidth and resources, since each server is doing the same work (polling devices, processing data).

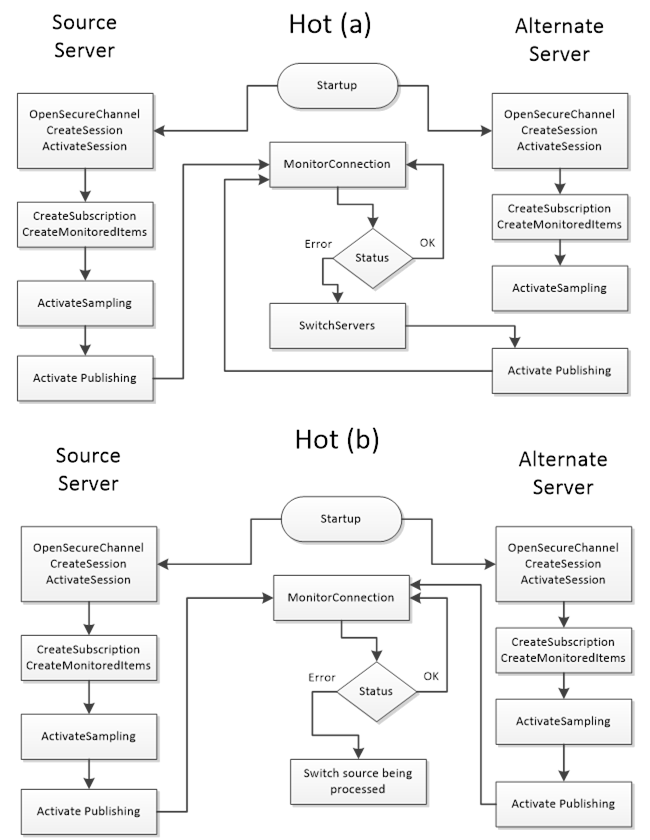

For OPC UA clients, hot redundancy is the most involved mode, because clients may choose to maintain subscriptions with multiple servers simultaneously. The OPC UA specification actually outlines two strategy options for clients in hot mode:

- Option (

a):One Reporting, Others Sampling. Theclient connects to all servers and creates identical subscriptions on each.However, it initially enables data publishing (reporting) on only one server (the one with highest ServiceLevel), while the other servers’ subscriptions are kept active in sampling mode only (they collect values internally but do not send updates to the client). If the primary fails, theclient then enables reporting on one of the backups(which already has a buffer of recent samples) and thus continues receiving data with minimal interruption. To make this seamless, the client should set a suitable queue size on monitored items so that any data changes during the failover window are buffered and can be delivered once reporting is switched over. This approach avoids duplicate data flow during normal operation butrequires the client to orchestrate turning reporting on/off per server.

- Option (

b):All Reporting (Parallel feeds). Theclient subscribes to all servers and lets each server report values concurrently. The client then receives multiple streams of the “same” data. Itmust filter out duplicates(for example, by using timestamps or sequence numbers to ignore older/duplicate values). The upside is that the client always has data from every server, so a failover is trivial – if one stream stops, the other is already providing data. The downside is increased network load and complexity in the client to reconcile parallel data. This approach might be used whenabsolutely zero data drop is desired and the data update rate is not too high, or when a client is sophisticated enough to merge data streams.

In either hot strategy, clients should also monitor each server’s ServiceLevel continuously to identify which server is considered “primary” at any moment. Typically, clients direct write or command actions to the server with the highest ServiceLevel (the primary) to avoid sending control commands twice. If a server fails, the client will see its ServiceLevel drop (often to 0) and will then interact with the next-highest server. Notably, automatic fail-back is not usually forced – if a failed server comes back, a client may or may not switch back to it immediately. The OPC UA spec suggests that clients should establish a connection to the recovered server, but not necessarily fail back automatically. It’s up to the application’s needs whether to revert to the original primary or continue with the new server as primary.

Hot And Mirrored Failover#

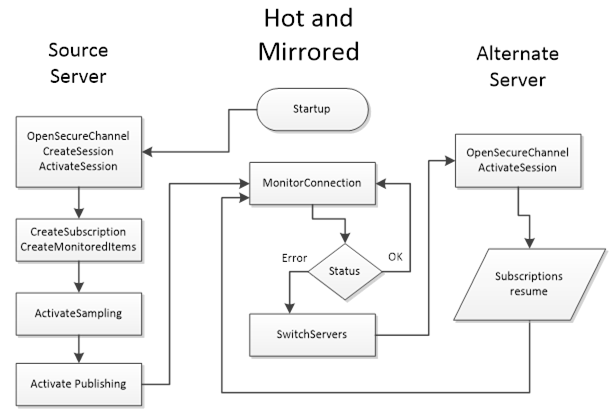

HotAndMirrored is the most advanced redundancy mode defined in OPC UA.

It combines the always-on approach of Hot standby with an additional twist: the servers actively mirror their internal state with each other. In HotAndMirrored mode, multiple servers can be fully active and in sync to the point that they share session information, subscription state, monitored item queues, and so on.

This means when a client is connected to one server, that server is propagating the client’s session and subscription state to its peer servers in the background. If a failover happens, the client does not need to create a new session or new subscriptions at all – the backup server already has an up-to-date copy of the session, including what data was being monitored. The client can simply switch the SecureChannel to another server and call ActivateSession, and the session continues on the new server as if nothing happened. This results in a seamless failover: no data needs to be resubscribed, and the client’s context is maintained.

In fact, with HotAndMirrored redundancy, a client typically only actively connects to one server at a time (unlike hot mode where it might connect to all) because it trusts that the servers are mirroring everything behind the scenes. The client might optionally keep secondary sessions open to other servers just to be ready, but it should not duplicate subscriptions on them (to avoid unnecessary load). Instead, it can occasionally poll the backups’ ServiceLevel or use heartbeat mechanisms to ensure they’re alive.

The benefit of HotAndMirrored is near-zero interruption and no need for reinitialization on failover – ideal for mission-critical systems that demand transparency and control. It effectively offers the transparency of a cluster (since the client’s session is preserved) while still being a non-transparent approach (the client is aware of multiple endpoints, but failover is very fast). Clients still initiate the failover (e.g., when they notice a drop in connection or ServiceLevel they perform the channel switch and ActivateSession), but this process is much faster than creating new sessions and subscriptions.

Due to all servers sharing the load of maintaining client state, this mode can facilitate load balancing: clients might connect to the server with highest ServiceLevel for reads/writes, and the system could distribute clients across multiple servers, since each server knows the others will mirror the sessions anyway. HotAndMirrored is the most resource-intensive and complex mode – servers must have a high-speed synchronization mechanism for state, and network and CPU overhead is higher to keep everything mirrored. It’s typically found in high-end systems (for example, redundant PLC pairs or DCS systems with redundant OPC UA interfaces) where maximum availability is needed.

This method is very similar to the transparent mode, it just delegates to the client the assignment of the server.

Client Interaction and Failover Mechanisms#

Designing for redundancy means considering both sides of the OPC UA communication: the servers must be configured appropriately, and the clients must know how to react. It also means understanding what is acceptable threshold for data loss and data recovery.

There are many aspects to consider when deciding not just the failover mode, but how to rollback into a normal state (fail-back). Some systems prefer a manual or delayed fail-back to avoid transitioning between servers. OPC-UA leaves this decision to the client/application design. A best practice is to allow the now-active backup to continue servicing until it’s convenient to switch back (for example, during a low-load period) or not switch back at all if it isn’t necessary. The redundant servers will update their ServiceLevel values as they change roles, so a client could detect when the original primary is healthy again (it might report a high ServiceLevel on return). The client may then either ignore it (staying with the current server) or orchestrate a controlled switch back to it, depending on requirements.

Security is another aspect to consider: clients must trust all the servers in a redundancy set. This means deploying the necessary SSL/TLS certificates or trust lists on clients for each server, since a client might end up connecting to any of them. The discovery mechanism (FindServers) helps here by providing application certificates of the alternate servers in the response, but an integrator should ensure the trust chain is in place in advance so that a failover connection isn’t blocked by an untrusted certificate.

Real-World Applications and Best Practices#

OPC-UA server redundancy is used anywhere reliability and uptime are critical and where the failure of the server does not directly correlate to a machine failure.

Common examples include large manufacturing lines, power generation and distribution systems, oil & gas facilities, building automation for mission-critical infrastructure, and other scenarios under the Industry 4.0/IIoT umbrella where data must always be available.

Consider a SCADA system monitoring a power grid: an OPC UA server polls hundreds of substations. If that server goes down, even for a few minutes, operators could lose visibility into the grid’s status. By deploying a secondary OPC UA server (perhaps on a separate physical machine or a fault-tolerant PLC module) in a redundant configuration, the SCADA client can instantly switch to the backup and continue receiving telemetry.

Another scenario is in batch manufacturing: an MES (Manufacturing Execution System) client might subscribe to a stream of quality data from an OPC UA server. Redundancy ensures that if the primary server or its PC reboots, production doesn’t have to stop; the MES seamlessly pulls from the backup server. In building automation, redundant OPC UA servers might interface with HVAC and security systems to guarantee that critical alarms (fire, intrusion, etc.) are always delivered to monitoring stations, even if one server fails.

When implementing OPC UA redundancy, here are some best practices to consider:

Match Servers 1:1 with Data Sources: Ensure your redundant servers have equal access to the data source. If you have redundant PLCs (primary/secondary controllers), it often makes sense to pair each OPC UA server with a specific PLC. If you have a single data source (single PLC), check if it supports multiple simultaneous OPC UA sessions for hot redundancy. If not, you may be limited to warm or cold modes. Design the architecture (including network topology) such that a failure in one component doesn’t cut off all servers. For example, redundant servers should ideally run on separate hardware or VMs, and if possible on separate network paths to the client (some systems use dual-network redundancy, where each server communicates over independent networks for higher resilience).Keep Configurations Identical: As noted, all servers in the set should have the same address space and data. Use configuration management to deploy the same OPC UA information model, namespace, and NodeIDs on each. If the server is pulling data from external devices, make sure the polling rates, timeouts, and item lists are the same. Any difference could lead to inconsistent data or client errors when switching. Also synchronize user permissions and roles across servers, so that a user/client authorized on one server doesn’t get denied on the backup. Essentially, treat the redundant set as a single system during configuration.Time Synchronization: Always synchronize system clocks of redundant servers. This will ensure that data timestamps and event times are coherent regardless of which server provided them. It also helps when the client is merging data streams or comparing sequences – if one server’s clock lags, its data might appear out-of-order. Using an NTP server or IEEE 1588 PTP on all machines is highly recommended. Furthermore, design your data collection with buffering in mind: if using hot or warm standby, consider configuring a buffer (queue) in subscriptions to catch data changes during the small failover window. This can prevent data loss at the client side.Test Alarm and Condition Handling: If your system uses OPC UA Alarms & Conditions, make sure to handle them correctly in a failover. As discussed, in Cold/Warm/Hot modes,event IDs won’t be synchronized between servers. This means after a failover, the client might not know which alarms are still active or which have already been reported. The recommended practice is for the client to call a ConditionRefresh on the backup server as soon as it connects, which forces the server to resend the current alarm states. This way, the client can reconcile any alarms that might have been missed or duplicated during the transition. It’s a simple step but often overlooked – integrators should verify that their client software performs this (many HMI/SCADA systems do a refresh on reconnect by default for this reason).Use ServiceLevel and Heartbeats: Leverage the ServiceLevel value and/or heartbeat mechanisms (such as a subscribed status node or heartbeat signal) to detect failures promptly. Ensure that theservers are configured to downgrade their ServiceLevel instantly on a critical failureif possible. Some OPC UA servers might evengenerate an Event or audit entry when failover occurs– if available, subscribe to those for logging or operator notification. Also consider exposing a diagnostic in your client UI that shows which server (primary or secondary) is currently active, so operators are aware of the system’s state.Plan the Failover Policy: Decide whether the failover should be automatic or manual. OPC-UA gives you the tools for automatic client-side failover, but in certain industries, operators prefer to manually confirm a switch to backup (to avoid false triggers). Similarly, decide on fai-back: will the system automatically revert to the primary when it’s back, or run on the secondary until a maintenance window? There’s no one-size-fits-all answer – it depends on the process criticality and stability of your servers. What’s important is to configure timeouts and thresholds in the client so that it doesn’t oscillate or switch unnecessarily. For example, you might require a server’s ServiceLevel to be bad for a few consecutive checks or a few seconds before declaring it failed.Document and Train: Document the redundancy setup for your operations team. This includes which server is primary, what the roles of each are, and how to force a switch if needed. Provide guidelines on how to bring a failed server back into the group (ensuring it has the latest data/state if required, before letting clients use it). Train personnel on monitoring both servers – for instance, a secondary server might silently fail and not be noticed until failover is needed, which is too late.Regularly test switchoverprocedures to make sure everything works as designed and to keep the team familiar with the process.

Final Thoughts#

OPC-UA server redundancy is a powerful feature for building resilient industrial systems. It also is increasing in demand as OPC-UA servers start being federators of multiple machines and aggregators of other OPC-UA servers.

I personally always suggest having a transparent redundancy. It is much easier to control your OPC-UA server, than all the OPC-UA clients that exist throughout your shopfloor. Also, remember that you may have some OPC-UA clients that support one mode and not the other. It is always preferable to handle this in a centralized way and remove that complexity from all the clients that may exist.

Nevertheless, by understanding the nuances of transparent vs. non-transparent modes and the spectrum from cold standby to hot mirrored standby, system integrators can design architectures that meet their uptime requirements. The key is clear planning: align the redundancy mode with your hardware capabilities (device connection limits, network design), and ensure your client applications are equipped to handle the chosen mode’s failover process. Modern OPC UA toolkits simplify a lot of this, but it’s still crucial to know what’s happening under the hood so you can troubleshoot and optimize the failover performance.

Remember that redundancy is not just about technology – it’s about operational continuity. Thus, always consider the operational scenario:

- How quickly do we need to recover? How much data can we afford to lose, if any?

- Who or what detects the failure?

The OPC UA standard provides a flexible framework to answer these questions, and with proper implementation, you can achieve near-zero downtime in the face of server failures. In summary, OPC UA server redundancy ensures that data keeps flowing even when servers don’t. By deploying redundant server sets and leveraging OPC UA’s built-in redundancy support, you can build industrial systems that are robust against failures. Whether you choose a straightforward cold standby or invest in a hot mirrored solution, the result is the same in principle: higher reliability and confidence that your critical data will always be available when you need it. With careful design and adherence to best practices, OPC UA redundancy becomes a dependable backbone for high-availability automation systems, keeping factories running, lights on, and processes under control even in the face of unexpected outages.

UA Part 4: Services - 6.6.2 Server Redundancy - https://reference.opcfoundation.org/Core/Part4/v104/docs/6.6.2 Transparent redundancy - Unified Automation Forum - https://forum.unified-automation.com/viewtopic.php?t=611 Redundancy - https://infosys.beckhoff.com/content/1033/tf6100_tc3_opcua_server/17803657739.html?id=4892807151891666650 Non-transparent Mode (non-transparent Redundancy) - https://docs.tia.siemens.cloud/r/simatic_et_200eco_pn_manual_collection_eses_20/function-manuals/communication-function-manuals/communication/communication-with-the-redundant-system-s7-1500r/h/using-an-opc-ua-server-in-an-s7-1500r/h-system/non-transparent-mode-non-transparent-redundancy?contentId=wSatTJReGHhcjO9sDY_tUA UA Part 5: Information Model - 12.5 RedundancySupport - https://reference.opcfoundation.org/Core/Part5/v104/docs/12.5 OPC UA Client - Redundancy - WinCC OA - https://www.winccoa.com/documentation/WinCCOA/3.18/en_US/OPC_UA/opc_ua_c_redundancy.html